“Darwinian theory, as used by evolutionary biologists today, is simple to state, difficult to apply, and astonishing to contemplate.” -RDA, 1978.

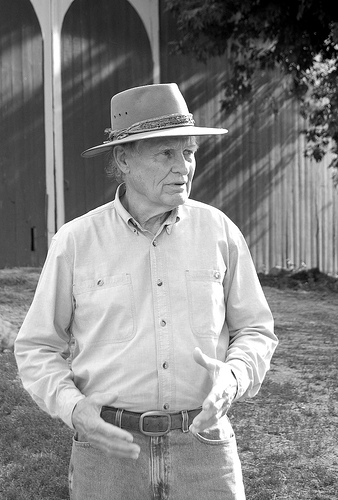

This website is devoted to the ideas and works of Richard D. Alexander (November 18, 1929 – August 20, 2018), the late T.H. Hubbell Distinguished University Professor of Biology and Curator of Insects at the Museum of Zoology of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, and elected member of the US National Academy of Sciences. Prof. Alexander was an evolutionary biologist whose research integrated the fields of systematics, ecology, and behavior. He was devoted to understanding the lives of organisms by pursuing thoroughly the explanatory power of natural selection. With extraordinary insight into the evolutionary process, Alexander developed wide-ranging hypotheses and drew out multiple layers of implication that provide effective and often challenging explanations for why organisms are the way they are. His favorite study animals were cicadas, crickets, naked mole-rats, horses, and humans.

the late T.H. Hubbell Distinguished University Professor of Biology and Curator of Insects at the Museum of Zoology of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, and elected member of the US National Academy of Sciences. Prof. Alexander was an evolutionary biologist whose research integrated the fields of systematics, ecology, and behavior. He was devoted to understanding the lives of organisms by pursuing thoroughly the explanatory power of natural selection. With extraordinary insight into the evolutionary process, Alexander developed wide-ranging hypotheses and drew out multiple layers of implication that provide effective and often challenging explanations for why organisms are the way they are. His favorite study animals were cicadas, crickets, naked mole-rats, horses, and humans.

Dick was a man of enormously broad interests, who loved horses, music, stories, and working with his hands. He was married to his loving wife Lorrie for over 60 years. This website is devoted primarily to his academic or professional work, although aspects of his life, character, and leisure pursuits can be glimpsed here and there, such as in his nonprofessional written works.

To begin, we’ll let RDA tell his own story. This is a summary of his curriculum vitae, largely his professional life, that he appropriately appended to his complete CV initially in 26 July 2003, where it remained as is through the last version of his CV in 2013. It is unedited except for my ellipses at the end, as I have contracted the description of his works in progress.

PERSONAL STATEMENT

After coming to Michigan in 1957, trained as an entomologist with interests in behavior and speciation, I was transformed into a general biologist by several years of teaching introductory zoology. During those years I worried considerably over the question why particular parts of the introductory courses were worth teaching or learning. Eventually I became so distressed about the course, as taught then (I was but a laboratory instructor), that I decided to conceive my own new course and propose it to the department head. I titled it “Animal Behavior and Evolution” because behavior was the topic in biology that most interested me, and I had concluded that whatever one did in biology it had to be developed out of an evolutionary framework and be consistent with current evolutionary theory. I was so determined about the proposal that I was prepared to leave Michigan if my course request was turned down. It was not, and I suspect that Dugald Brown, a perceptive department leader, was instead concerned that I had taken so long to make such a request. When I began this course, in either 1960 or 1961, there was no course in evolution and none in animal behavior at Michigan. In all likelihood, neither topic was a central theme in any biology course, in a modern sense, and they were naively and erroneously used in the introductory zoology course. Today is a striking contrast: At least three formal courses and numerous seminars are taught in each subject, each is heavily involved in the introductory courses, and each is considered seriously in probably most courses and seminars in the Department of Biology. In addition, several of the principal theorists in this arena, William D. Hamilton, George C. Williams, John Maynard Smith, and Mary Jane West-Eberhard, have all served as distinguished visiting professors in the U-M Museum of Zoology. Hamilton was a curator in the Museum of Zoology for seven years. Specialists in behavior and evolution have now been hired in Psychology and Anthropology. Other staff in Philosophy, Political Science, and Psychiatry are also formally involved, and several meetings or programs of university- or college-wide significance have been held on the relationships of behavior and evolution. One of my doctoral students in biology, Beverly Strassmann, was hired, and is now a tenured faculty member, in the U-M Department of Anthropology.

When I began teaching animal behavior and evolution I had no idea how to relate the two topics; I only knew it had to be done somehow. Beginning with the first several years that I taught this course, my research and that of my graduate students has been influenced greatly by my efforts to understand behavioral evolution. In the mid-1960’s the theoretical contributions of George C. Williams and William D. Hamilton — on kin selection, sociality, levels of selection, sex ratios, and senescence — created for me (and the rest of biology) the synthesis I was seeking; in the early 1970’s Robert Trivers added important theories on social reciprocity and male-female interactions in connection with parental care. During the decade of the 1970’s I divided my teaching between Behavior and Evolution and Evolutionary Ecology (with Don Tinkle), the latter representing another new direction in biology stimulated partly by the people already mentioned, and by Ronald A. Fisher and David Lack. Also during this period I began to believe that I might eventually realize a goal that had been with me since undergraduate days: significant new insights into human behavior as a result of biological theory and knowledge. I introduced this topic into my courses and seminars, published about 25 papers on it, and in 1979 published Darwinism and Human Affairs, following by eight years an initial paper in this arena titled “The Search for an Evolutionary Philosophy of Man.” In 1981, I screwed up my courage and offered a new course, “Evolution and Human Behavior.” To me the course was as exciting as the first years of Animal Behavior and Evolution, and perhaps it was almost as confusing for the students. I committed myself to exploring this topic in greater depth in my teaching and research, and in this connection in 1987 published The Biology of Moral Systems. In the 1970’s, in conjunction with Professors Napoleon Chagnon and William Irons, anthropologists at Northwestern University, a few professors at Michigan began twice a year meetings to discuss evolution and human behavior with our two groups of students; some of the Northwestern students had been undergraduates in my courses at Michigan. We soon added the Canadian psychologists, Martin Daly and Margo Wilson, and subsequently invited academic people from throughout the Midwest. In 1985, with the help of funds granted by U-M provost Bill E. Frye, six colleagues and I at Michigan established an interdisciplinary program in human behavior through the Rackham Graduate School. This program helped both graduates and undergraduates, and utilized and coordinated the core of excellent staff now established in the social and biological sciences in the area. A parallel program has been established since by Professor of Psychiatry, Randolph Nesse, sponsored by the U-M Institute for Social Research; Nesse sat through my course years before, was a member of the original Human Behavior and Evolution Program, and eventually was instrumental in establishing the international Human Behavior and Evolution Society. At Michigan, human behavior and evolution will be represented in the new programs initiated in conjunction with the Life Sciences Initiative begun in 1999.

Since graduate student days I have accepted that the special kinds of knowledge that come from systematic and comparative study play a central role in the contributions of evolutionary biology to human self-understanding, hence to the alleviation of strife and misery and, eventually, the generation of a more nearly universal freedom and happiness in human existence. Said differently, I have a strong feeling that our ability, as a species covering and controlling the planet, to resolve in acceptable fashions the growing array of moral, ethical, and other behavioral problems that confront us will be aided significantly by aspects of self-knowledge that biology alone can provide.

Four aspects of my research are neglected in the above account. First, since 1953, I have almost continuously studied the systematics, biogeography, and behavior of crickets and other singing insects in many parts of the world, for 20 years typically in the company of my former student and postdoctoral associate, Daniel Otte. The part of this work in which I have been involved has resulted in the location of over 1,000 new species, description of approximately 426 new species and genera, and discovery of several kinds of special problems in speciation. Second, for about 20 years, four of my students and I have been involved in the effort to understand the evolution of “queen-worker” sociality or eusociality. In 1975-76, I developed a basic hypothesis and established a series of 14 specific predictions regarding eusociality in a hypothetical vertebrate, which proved uncannily correct when we later discovered that there indeed is a eusocial mammal; as a result, between 1979 and 2000, three doctoral students and I studied colonies of the naked mole rats of Kenya in our laboratory at Michigan. Third, with two doctoral students and a postdoctoral associate, I initiated in 1992 a 17-year intensive study of the geographic connections between the three 17-year cicadas and the three (now four) 13-year cicadas across the state of Illinois. Fourth, I have initiated an effort to develop a coherent picture of the social behavior of horses and other Equidae, including an analysis of the horse-human interaction from the viewpoint of a behaviorist and evolutionist. The central aspect currently is a 16-year study of my own breeding herds.

**********

I am using my retirement period, which began January 1, 2001, primarily to write and publish non-scientific material involving…

…stories, verse, and drawings involving people and events in the history of the two townships in which I have spent most of my life: Sangamon Township in Piatt County, Illinois, and Freedom Township in Washtenaw County, Michigan

…stories, verse, and cartoons from academic life

…autobiography

…texts and illustrations for children’s books

…writings on the social behavior of horses; the genetics, breeding and promotion of horses; training; the horse business; and the horse-human interaction

…stories, songs, verse, and cartoons about horses and horse people

A meeting in 1987 of several of the thinkers who were responsible for the modern unification of evolutionary and behavioral science. Left to right, in the back: David Buss, George C. Williams, Martin Daly, and Mildred Dickemann. In the front, William D. Hamilton, Napoleon Chagnon, and Richard D. Alexander. The three absentees when comparing this group to RDA’s personal statement above are Robert Trivers, Bill Irons, and Margo Wilson, who took this photograph.

This website was launched in June 2010 and is a work in progress.

Thanks to David Buss for the group photo and Mark O’Brien for the black and white photos of Dick here and elsewhere on this site.

For more information or to become involved, contact David Lahti at dclahti@gmail.com.